If you’ve trained Brazilian jiu-jitsu for any appreciable amount of time, you’ve had injuries.

Personally, I consider myself one of the more fortunate. Sure, I’ve had the occasional malady, but I have been lucky to avoid a major injury that would require surgery. Besides the pain and expense — as much it galls me to admit this — I don’t want to take the time off from training that a major injury would require.

One of the first pieces of advice I try to tell the new guys who go too hard is that injury is the real enemy: if you want to get better at jiu-jitsu, staying on the mats is job one. Especially for a guy who weighs 138, turns 40 this year and trains regularly, I’ve been very lucky.

That’s what I keep telling myself this month. Leading up to the New York Open, I had a nagging foot injury that I trained through. At the tournament, I re-injured it during my finals match. Now, every time it gets manipulated in the wrong way — even gently — it becomes debilitating.

But there’s the Catch-22: you can’t train without risking injury, but part of the reason you want to avoid injury is so you can keep training, especially with a tournament (like, say, the Mundials) coming up. Where is the line between being tough and being stupid?

The answer I’ve come to is that you must evaluate two factors: risk of re-injury and reward of training. When you’re nicked up, which is how I’d classify my current injury, you can still train some things. For example, one of my training partners hurt his knee and spent his healing time working half-guard. You also must evaluate your ability to protect yourself while drilling and rolling, and figure out whether you’re taking too great a chance on setting yourself back.

Naturally, figuring this out depends on the severity of an injury. I’ve had back injuries that were simple stiffness and would loosen up once I got moving, and back injuries that I’d have had to be a lunatic to train through.

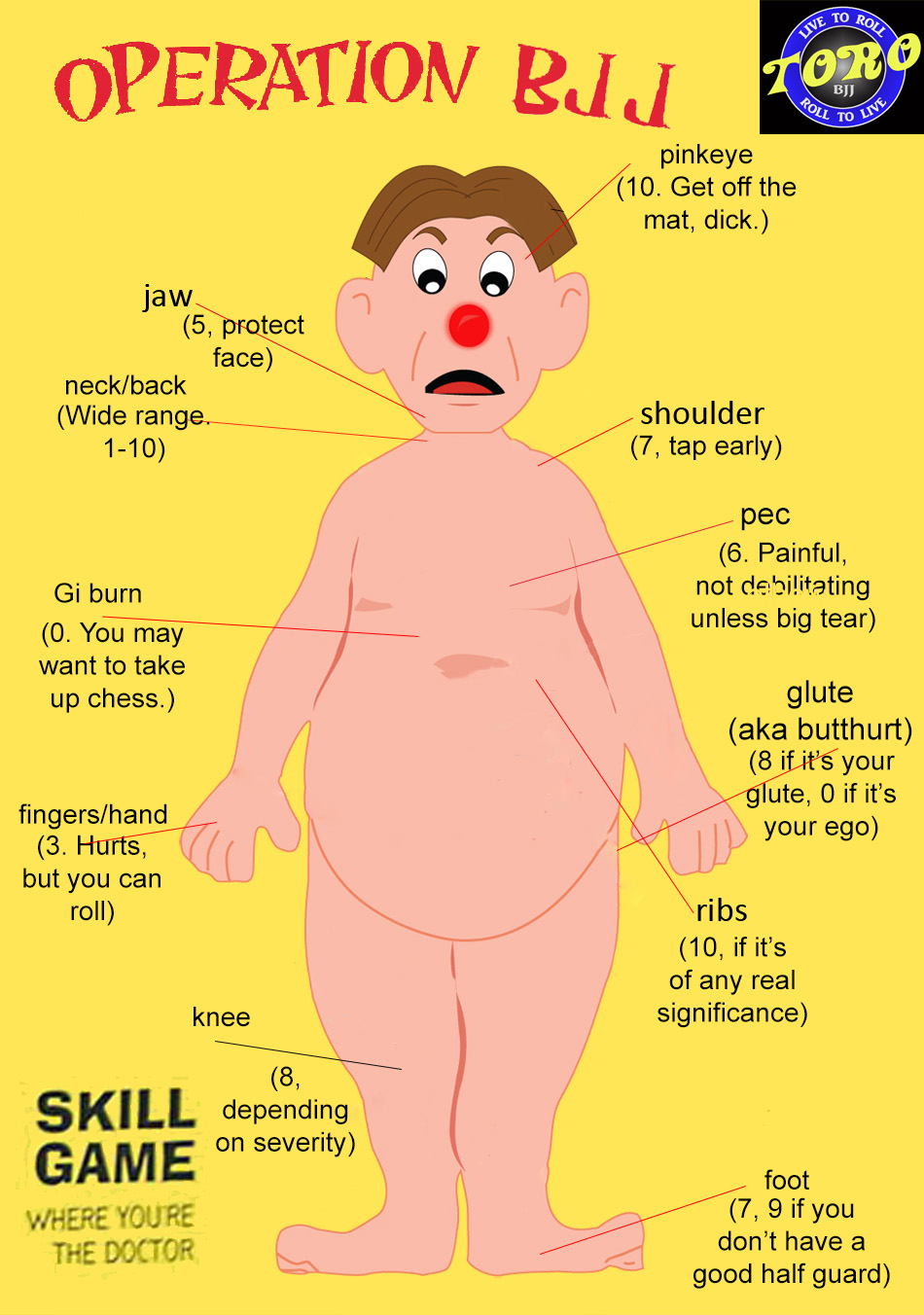

Given my various experiences with being nicked up, I’ve often been surprised at how easy some injuries are to train with and how hard others are. I do a lot with gi grips, for example, but finger and hand injuries are relatively simple to train with. You can wrap ’em up and hide the injured hand. (In fact, at least one person reading this has choked me using only one hand).

The opposite end of the spectrum: rib injuries. I’ve had two ribs pop out. You use your core for everything, in jiu-jitsu and in life. One of my rib injuries was extremely painful and fairly debilitating. The other one didn’t hurt much. But then I tried to sit up and couldn’t. This foot injury has shown me — again, stupid as it sounds — just how much you use your foot, both in guard and on top. It’s harder to hide than you’d think.

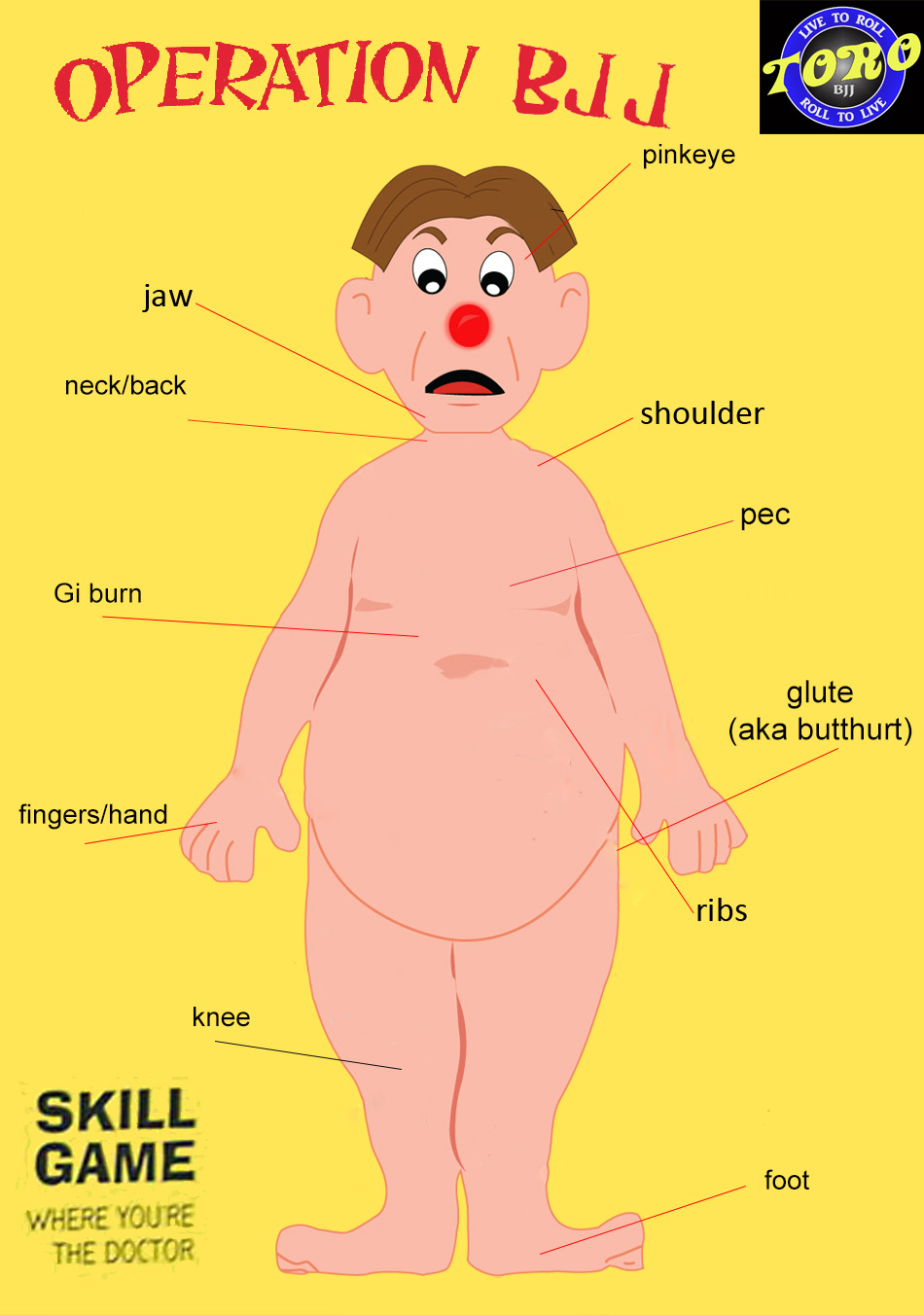

After musing on which of my little bumps and bruises were hardest to train with, I made this graphic rating the injuries on a scale of 0 (a cakewalk) to 10 (sweet merciful crap, maybe we’ll stay in bed and watch videos).

This is just my own experience and is not meant to be taken very seriously. The only medical advice I feel comfortable giving is “you should eat right and train jiu-jitsu.”

There shouldn’t be many surprises here. The big muscles and joints are always big problems. I also always think it’s worth noting that if you have an infection, that’s a 10 and you should stay home, period: I raise an eyebrow at how many folks don’t get this.

One notable rating, and this might be a function of the severity of the injury: I personally found it easier to train with a messed-up knee than with a messed-up foot. Obviously, my knee injury wasn’t a major thing, but I was able to change up the things I was doing fairly effectively to protect the knee.

With the foot? Can’t be on top, you’ve got to stand on it. Can’t really keep the guard closed, and with open guard, you either have to step on hips and biceps (ouch!) or try to hide that foot by putting it further away from your opponent — which means you need to shrimp off of it (also ouch).

We all have strengths and weaknesses. In terms of the old remedy of Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation, my ICE game is tight, and the rest I have a problem with. (See what I did there?)

The old saying goes, “If you wake up one morning after training and nothing hurts, you died.” My hope is we all start to prove that saying wrong. Happy and healthy training to all of you.