Education is important. Nelson Mandela called it the most powerful weapon people can use to change the world, Abraham Lincoln said it was the most important task we could engage in as a people, and I say it’s the most important tool I’ve seen to improve the lives we all live.

Investing in education almost always pays off, for individuals and nations.

By the way, I use the term “education” broadly: some of the smartest people I know didn’t graduate from high school, and some of the dumbest have Ph.D degrees. If this sounds like a poetic exaggeration, I assure you I mean it literally. There are many ways to educate and improve yourself, with academic work being just one of them.

This month, after almost exactly four years of hard and consistent training. I earned my purple belt. I have a long way to go in my jiujitsu journey, but I’m so happy to have taken this step. The four-year mark is a nice coincidence, since it coincides with the amount of time it takes most people to complete something most people identify more clearly with education, an undergraduate college degree.

I have one of those, and believe me, I worked way harder to get the purple belt than I did to get my Bachelor of Arts. Sorry, professors, but it’s true.

My mom always valued education, so she made sure I finished my undergrad degree. Later, I went on and got a Master’s, and earned an honor or two along the way. I don’t talk about that stuff a lot, and the only reason I’m doing so now is to put it into context.

This is the context: it’s no exaggeration to say that I’m as proud of this belt as any of that academic work. It took that much work and that much sacrifice.

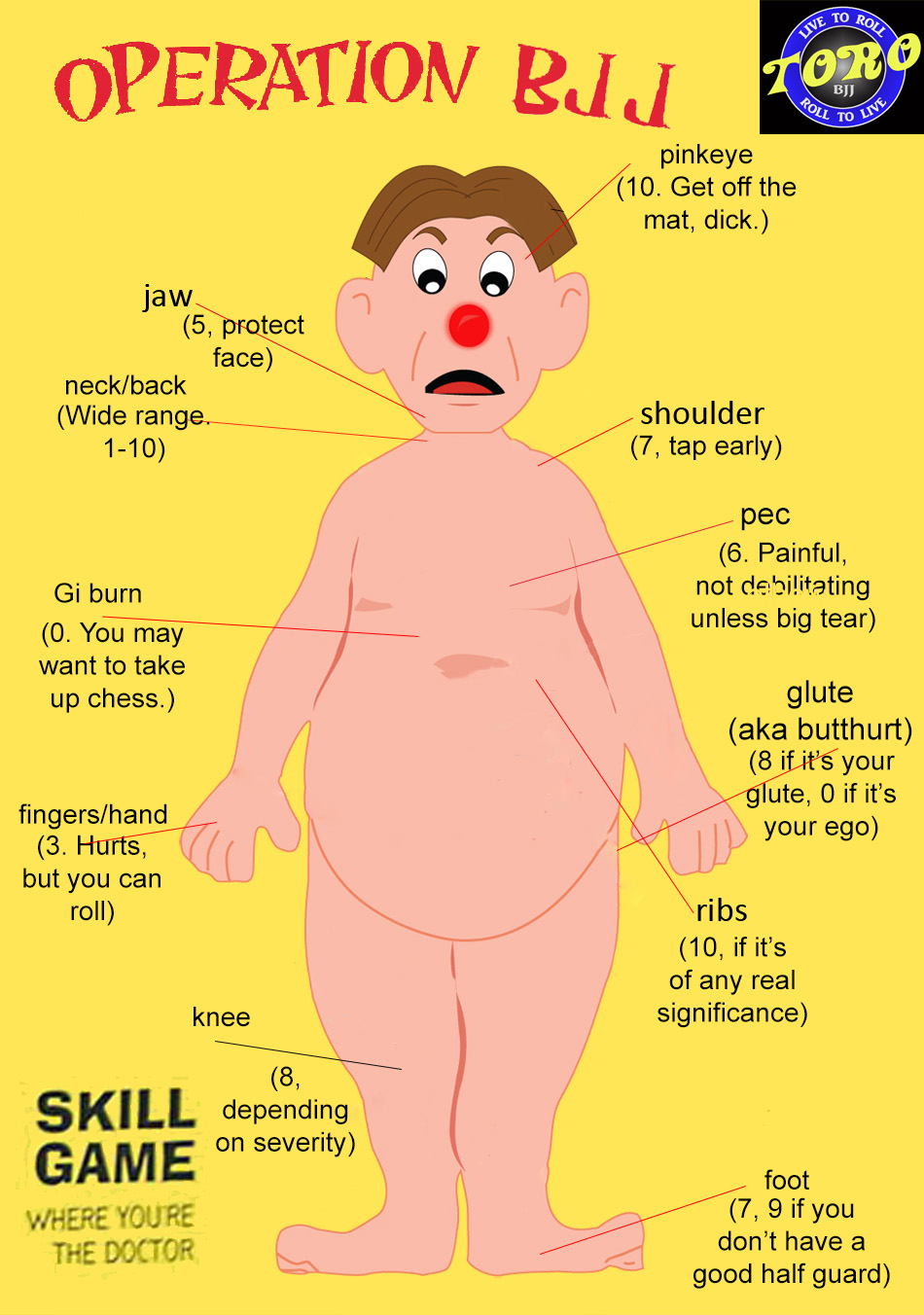

In order to obtain an education in jiujitsu, I had to make several investments: a lot of time, a ton of sweat and pain, and of course some money.

When I graduated from college in 1998, in-state students attending public four-year colleges paid $3,243 on average in tuition and fees. It’s a lot more now (and frankly, I think college should be free, as it is in many other countries).

That investment has paid for itself many times over in life experiences, in jobs I couldn’t have gotten without the degree. As the great musical philosopher Tom Lehrer once said, “Life is like a sewer: what you get out of it depends on what you put into it.”

I already told you that I had to work harder to get my purple belt than I did to get a college degree. Factoring in gym dues, seminars, privates, instructional materials and expenses from competing at tournaments, I’m fairly sure I spent more money along my path to purple belt, too.

(If anyone is really interested, I can break out those calculations. I frankly never even thought about it until now: when you’re doing something you love, you just kind of do it.)

Getting a black belt takes more than 10 years in most cases, time that’s roughly equivalent to getting a Ph.D. To me, the comparison between jiujitsu education and advanced degrees just illustrates the value of learning jiujitsu: the achievements we’re proudest of are the ones that are hardest to accomplish.

For students, we have to accept early on that getting where we want to go requires commitment. Why, then, do so many jiujitsu students shortchange themselves — and try to shortchange their instructors — on their martial arts education?

There are two parts to what I’m trying to say: the part that involves us as students of jiujitsu and the part that involves the way we relate to our instructors.

Primarily, what I want to say is this: as students, we should be maximizing our return on the investments we *do* make. If you’re paying dues to your school, why not take advantage of all the classes that are offered? It costs as much to train twice a week as it does five in most schools. Training as much as you can maximizes your return on investment.

Everyone has their own path to walk, and we all have different resources at our disposal. I’m not just talking about spending money here. Not everyone is fortunate enough to have the disposable income to go to every seminar, buy every DVD set or take privates consistently.

That’s why it’s important to acknowledge that there are different types of investments. Can’t afford seminars, but have time to stay after class? Get extra drilling in. Time is the most important investment you can make. Don’t have access to the gym? Do a spreadsheet or a mind map of the techniques you know. Jiujitsu is a long journey, but the more time you’re able to put in, the quicker and more rewarding it is.

The second part of this involves our instructors. This is a little trickier, as it always is when art and commerce intersect.

If we value a college education enough that we’re willing to spend tens of thousands of dollars on it, though, why wouldn’t we place a similar value on our continuing education in jiujitsu?

It’s tough to make a living running a jiujitsu school, and I’m always surprised when people do things like get out of paying gym dues. To a certain extent, I understand — everybody’s trying to get by, and since your instructor loves jiujitsu, he probably wants people to train.

Keep in mind that your instructor has to make a living, and your school has to stay open. If you like training, that’s a shared interest that’s well worth preserving.

Invest in your education, whatever path that takes. And invest in the people that help you keep learning. We all get better that way.