For the past week, I’ve been watching closely for motorbikes zipping around me in any direction, improbable lane changes and aggressive double parking. I’ve been honked at for stopping at a stop sign, cut off by not one but two pedestrians strolling their children, backs firmly placed to the rush hour traffic. By the time I pulled into the gas station and saw the guy smoking while pumping his gas, I almost welcomed the oncoming explosion.

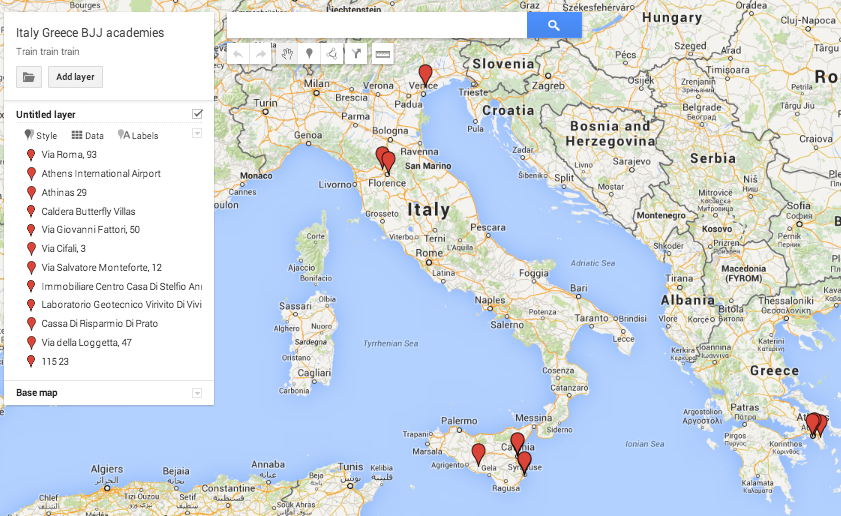

Here’s a time-lapse photo series that gives you only the barest idea of what this driving experience was like:

But it got better.

Why did it get better? I flew into Catania a week ago with the plan to spend a few days here at the beginning of my driving tour through the largest Mediterranean island. During those few days, I saw all of the above multiple times, plus a guy in a full wrist-to-shoulder cast use his crippled wing to hold his phone while he screamed into the receiver — all the while weaving through traffic in full defiance of lanes, laws and common decency. For obvious reasons, I walked a lot.

Once I got out in the country, the degree of difficulty diminished considerably. Partly, this was because the rural environments were less crowded. Upon returning to Catania it occurred to me that I’d picked the deepest end of the pool to start with: flying in to a busy university town after dark and trying to find a tiny road that even locals hadn’t heard of.

I drove back to Catania in the middle of rush hour today, though, and I noticed something: I was still a tourist, but I was able to get into the flow of traffic better. Little old men were only cutting me off when I let them. I could identify a valid parking space and capture it with minimal trauma.

This made me think about jiu-jitsu. Not just because everything makes me think about jiu-jitsu, although of course that is also true.

The gym where I train has grown a lot. When I started, there were perhaps 10 serious regulars at the classes I attended. I had no idea what I was getting into, and back then we all rolled after our first class.

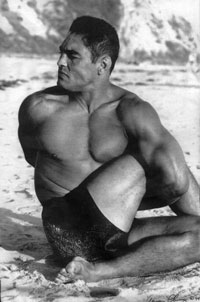

My first rolls were with my instructor; a very successful pro MMA fighter (he’d heard I’d wrestled a year in high school, so we started standing); a monster wrestler who was a three-stripe blue belt at the time; and a then-purple belt who has crushed tournaments ever since I’ve known him. I can’t recall if I rolled with the future blue belt world champion at my first or second class, but it was one of the two. There weren’t many other white belts, and there certainly weren’t any that I was better than.

It went how you’d expect. This was the deep end of the pool. This was driving in Sicily.

I trained a while. Got crushed every night. I was having too much fun learning things to be upset about the litany of kicking that my solitary ass took.

In the coming months, I was still at the bottom of the ladder, but the sink-or-swim situation I was in forced me to get a solid grounding in the fundamentals. First I was still getting passed easily, but I knew when to shrimp. Then I was still getting mounted but I knew to keep my elbows tight. Maybe I’d see my opponent do something that I had no idea about, but I knew to protect my neck and face.

This was real progress! When new white belts came in, even the really big and strong ones had a tough time submitting me. I had a lot of practice trying (and mostly failing) to survive against bigger, stronger, more skilled people. This was a huge help that I’m still thankful for.

[Note: I have mixed feelings on whether it’s good for new people to roll their first week. Generally, I think Roy Marsh has a solid philosophy on this: people wait to roll until they have some basics, and he has a standard safety spiel before each rolling session. But that’s the subject for another post. Anyway, the deep-end experience was good for me, but might not be best for most folks.]

I mention degree of difficulty, too, because it’s important to have training partners that challenge you, push you and tap you. We all know the White Belt Hunter: he’s the guy who gets his blue belt and looks around the room for less experienced, ideally smaller people, never realizing that those people are getting better at a faster rate than he is. Making progress — especially early, but at every stage of the game — requires skilled, tough partners.

The progress in my early jiu-jitsu life mirrors my return to Catania. I’m still overmatched driving here, but I know some basics I didn’t know before. It makes getting around easier, less stressful, and more fun.

The first time I successfully cut off that driver who was trying to get over on me and laughed at the guy who hesitated and was lost reminded me of my first successful escape from back control: yes, you’re better than I am, and yes, this is a small victory in the grand scheme of things. But this small victory is helping me improve — and helping me become a better training partner.

I still train with all of the people who I mentioned at the beginning of the post. They’re still all better than I am. Rolling with them is more fun than it’s ever been, though, and more productive for all of us.

Why am I writing this? Perspective. Our near-term goals don’t have to be to beat everybody, or to speak a language fluently, or to drive like a local (n fact, please don’t drive like a Sicilian local). I don’t miss getting my face smashed every night, just like I don’t miss feeling utterly lost on the roads. That time investment helped me build a foundation, and I recognize that.

Keep focusing on building that foundation, and your journey will get more enjoyable with each step. Even if you have to step into the deep end of the pool.