The 1 Minute Vegan: Addictive Almond Spread

This spread & dip is ridiculously addictive, easy to make, and great for after training (or any time). The hardest part is not eating all of it right away! This is one in a series of one-minute videos about how to make awesome, healthy foods for training that are also vegan. Thanks to executive producer Betsy O'Donovan for being the brains and taste buds behind these. Any screw-ups are mine, but you knew that anyway.

Posted by Dirty White Belt Radio on Friday, September 30, 2016

VIDEO: How to Make the Best Juice Ever

How to Make the Best Juice Ever

If you could watch a one-minute video and learn how to make the best juice I've ever had — juice that has profound, scientifically proven health benefits — you'd do it, right? Check this out and your taste buds, brain and your whole body down to your tendons will thank you.

Posted by Dirty White Belt Radio on Monday, September 26, 2016

Video: Training Soup (Vegan)

Eat Clean With Jeff's Favorite Training Soup

Eating clean (or trying)? Make Jeff's favorite training soup, a delicious, nutrient-dense and spicy little number that looks beautiful and is packed with fresh goodness. The ingredients are also affordable — and yes, it's vegan. This will keep your body healthy, your belly full, your wallet fat and all of you on weight. Full recipe and nutrient details in a separate post, and in the comments!

Posted by Dirty White Belt Radio on Thursday, September 22, 2016

Video: Two Great Juice Recipes

One amazing juice & one that might be gross

Nutrition matters! Here's a green juice Jeff makes after a night of hard sparring that's delicious — and one experimental juice that might be gross. Is it? LET'S GO TO THE TAPE.

Posted by Dirty White Belt Radio on Monday, September 19, 2016

VIDEO: What does your BJJ belt mean to you?

What Does Your BJJ Belt Mean To You?

What does your belt mean to you? We got great voicemails, from blue to black belt, explaining their answers — and we got some great photos of tattered old belts and video from promotion ceremonies, too. Check them out here!Featured: Daniel Charles Frank, David Porter, Ethan Daily, Anthony Elbert, with video & photos of Chela Tu, Jessica Lancaster, Hameed Sanders, Tim Hufford & many more.

Posted by Dirty White Belt Radio on Wednesday, September 21, 2016

Video: Your Job As a Blue Belt

This Sunday's guest, Royce Gracie black belt Jake Whitfield, talks about what blue belts should be doing in training. Sunday at 10 a.m., Jake reveals who his toughest MMA opponent was, what the hardest day of training in the barn looked like, what a judo pin has to do with stabbing someone in the neck, and what the most common training mistakes are. He also calls at least one of his students a sissy. Tune in to find out which one.

Posted by Dirty White Belt Radio on Friday, May 6, 2016

VIDEO: Why Smiling Matters

We did a segment about the charity project Mazi Heydary's son Ali is working on. it kind of got buried in the show, so I made a video. Please spend 5 minutes watching this! I'm matching the first $250 of donations here.

Posted by Dirty White Belt Radio on Monday, March 21, 2016

How A Critic Is Different From a Hater

In that moment, I was as mad as I can remember being.

I was at a major tournament with a bunch of people from my school. One of my good friends and teammates was about to compete (I won’t say names, so as to obscure the details, since the principle isn’t about this specific incident). He was competing against a highly-regarded competitor from a major competition school. The two competitors were ready to step on the mat, and I was preparing to coach and yell support.

What I wasn’t prepared for: a large upper belt from the other guy’s school starting to talk loudly about … well, let me just quote:

“Our guy is going to crush this guy,” he said. “I mean, LOOK at him.” He continued from there. It got progressively more disrespectful, and although this guy out-ranked me and out-weighed me by a fluffy 100 pounds, it started to feel like he was the Chester half of Chester and Spike. He went on about how our guy looked compared to his guy. Eventually, I asked my roommate to stand between me and this guy so I wouldn’t say or do anything stupid.

The match started, and the fluffy brown belt kept talking — until it became apparent that this would be a tough match after all. At about two minutes in, he stopped talking altogether. The match was neck and neck the whole way. My teammate wound up losing, but it was a terrific performance, and I was proud, and the portly gentleman was both much relieved and much quieter. He exhaled, did a small celebration, but there was none of the mess-talking that had been so present before.

Then came the moment that solidified in my mind that I would one day tell this story. One of Fluffy Brown’s teammates asked about when they’d see him compete.

“Oh, I’m basically a hobbyist,” he said. “I train twice a week, and I don’t compete any more.”

After I heard that, I had to take a walk.

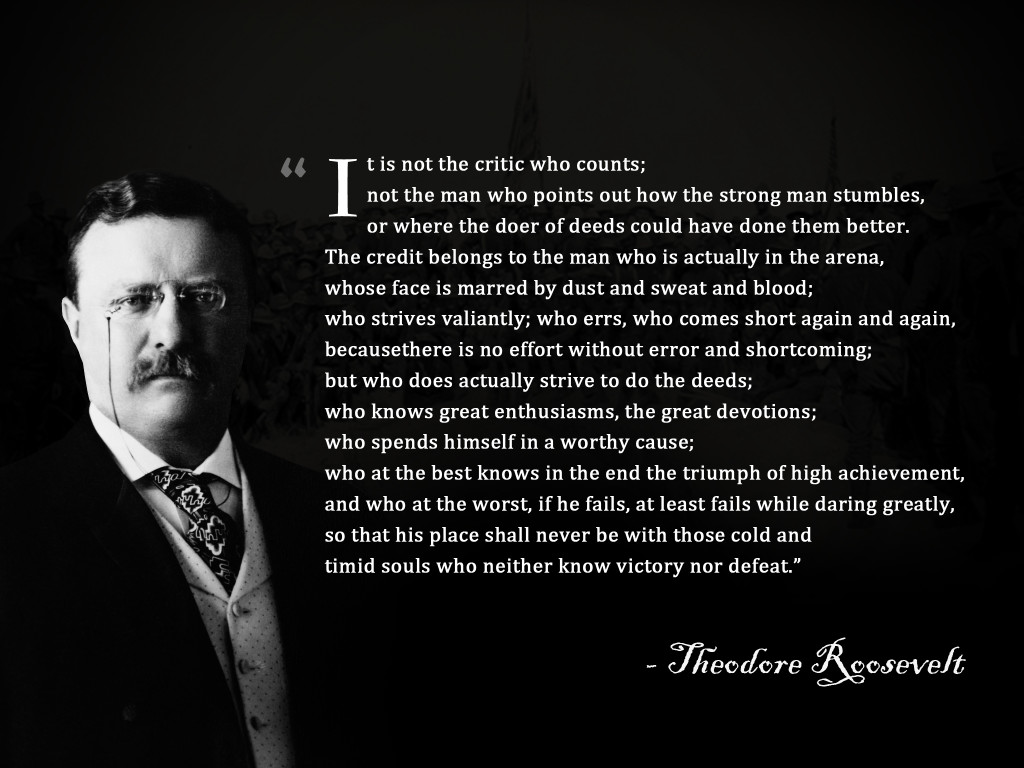

You’ve no doubt seen this quotation from President Theodore Roosevelt before. That’s because it’s classic, and it expresses numerous important ideas. Foremost among them is that it’s better to come up short again and again that to simply point out “where the doer of deeds could have done them better.” If we want to build great things, we have to try, and we usually have to fail at first. As the playwright Samuel Beckett put it: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

I want to make a clear distinction here. Though Roosevelt uses the word “critic” here, I don’t think the guy I’m describing counts as a critic. I would use a different word, a word that is thrown around a lot, and is often overused and misapplied. That word is hater.

Critics, in fact, are valuable. No one is above criticism. In fact, we should welcome good-faith criticism. It’s how we learn and grow.

When your instructor tells you to stop taking top position against new people, that’s not hate: that’s identifying the next step in your evolution. When a visiting black belt takes the time to explain why you’re not finishing from the back, it can feel like a scolding, but it isn’t. It’s a learning opportunity. It’s criticism, not hating. A good critic is invaluable, because a critic identifies flaws in your approach — and flaws can be fixed.

A critic has the doer of deeds’ best interests at heart. A good critic tells you where you’re making mistakes in open guard positions so you can fix those mistakes. A hater doesn’t deal in good faith: they point out the weaknesses in your open guard (or career, or life) so they can feel better about their own.

A critic advances us towards becoming our best self. A hater tries to tear us down to their level. Your coach is a critic. Your supportive teammates are critics. The guy who makes fun of you for trying is a hater.

It’s important not to confuse the two. A good high-profile example of confusing the two came recently when Rener Gracie penned a note entitled “to the loyal haters.”

Gracie University has come under a good deal of scrutiny over the past few years, first for online belt promotions. More recently, it’s been because of the rapid proliferation of schools with lower-belt instructors.

In Rener’s note, he refers to the folks scrutinizing the way Gracie University has developed as “haters.” That’s not accurate, in my view. Of course, there are some people on the Internet that will take any opportunity to take pot shots at anyone. Many of the people who were concerned about the online belt system, though, were respected black belts. And even people who think a Certified Training Center run by a blue belt might be a good solution for a rural area with no legitimate training for 100 miles — I count myself among these — think it’s a terrible idea to drop a blue belt who has studied mostly online right next to a school run by Gracie Jiu-Jitsu black belts and pretend like there’s nothing wrong.

Notice what these have in common: each has a solution. People have legitimate concerns about online belts? You can modify or end that program. People think that a mostly-online blue belt shouldn’t be represented as equivalent to a 10-year black belt? There are structures that can be put in place to guard against that.

None of this is possible, though, without being open to critics — not haters, but critics.

Sometimes, folks like to think they have haters. If you’re being singled out for criticism, you’re special. You’re different. You’re important. And if you are these things, then any critique of your work is simply hating.

There are two problems with this. First, it doesn’t necessarily reflect humility. We all can make mistakes, and few of us are so important that people are going to sit around thinking of meritless criticisms.

And I think most people do operate in good faith. I think more people want to help you than want to hurt you. I think you’re not much different than anybody else, trying to get better at something you like doing, and the people criticizing you aren’t hating so much as trying to demonstrate they have something to offer. I think Morrissey was wrong.

What, then, is hating? Hating is when you’re not critiquing in good faith. It’s when you’re criticizing Rener Gracie just because of who he is, rather than the way he’s going about his project. It’s when someone tries something new and, instead of honestly interrogating the project to see if it’s worthwhile, you treat the project like Rick James treated Eddie Murphy’s couch.

If you’ve noticed, there’s a fine line to walk here. I don’t think that only people who compete have a right to criticize others (although if you don’t compete at all, you might shy away from criticizing other people’s teammates in front of them during a tournament); instead, I think that criticism should come from a constructive place. On the other side of things, I think people who create things need to be open to critical thoughts from observers.

Here’s the most important thing. If you take only one thing away from this post, I would have you remember this:

It’s easier to destroy than it is to create; tearing things down is also quicker than building them.

If we want to have good things in the jiu-jitsu community, we have to not be quick to tear down the people who try to build them. If we want to have great things in the jiu-jitsu community, the people who build things have to be open to hearing what might make their efforts better.

VIDEO: Fluffy Carb Theory of Nutrition with John “Bagels” Telford

Fluffy Carbs: Bagels explains fight nutrition

Learn your nutrition science! Listen to John "Bagels" Telford explain the difference between fluffy carbs and sticky carbs.

Posted by Dirty White Belt Radio on Monday, January 18, 2016

Making the Mind Empty in the Surf

Surfing and martial arts share much. Top-level practitioners, for one thing: a healthy percentage of the Brazilian black belts I met grew up surfing, and professional surfers like Joel Tudor have taken up the gi with great enthusiasm and success.

You can see why, since both arts require adaptability and grace in the face of powerful opposing forces. The ocean’s tougher than all of us.

Another point of commonality: the experience that surfers (and psychologists) call “flow,” that optimal experience of life. Jiu-jitsu people use the term “flow” sometimes, too, but it’s more typical in the circles I run in to hear it called “mushin,” a Japanese word that roughly means “empty mind.”

There’s really no experience like it. I got it when I was doing competitive debate during high school and college, and haven’t had it since — until jiujitsu.

Putting this type of experience into words is a weighty task. I won’t make too strenuous an attempt, because it seems contrary to the very notion of an empty, flexible mind. I’m merely going to describe how it seems to me during a perfect sparring or competition experience.

They come for you and grab you, hard. You off-balance them and then you’re on top and they don’t know what happened. Things are slow, slower than life ever is. They try to grip you again, and you watch their hand come open as it reaches for you. It could take what seems like a second or what seems like a year, and you know where on your body it will land precisely.

But you’re not there any more. The hand’s efforts are useless. Then you let them grip you, just to show them they shouldn’t grab you there, and suddenly they’re tapping.

I don’t use the word sublime a lot, but not much else qualifies. The world is gone. Life is right here.

***

We often talk about martial arts as a practice, and other disciplines from sporting to religious to philosophical use that same terminology. The end results you’re aiming for with these disciplines differ widely. It’s the practice that brings focus, clarity, and the ability to experience what we call flow. It took me years to get there in both debate and jiu-jitsu, and I’m certainly not there every session. But, as with yoga or music or whatever your art of choice is, it’s the practice that matters.

Buddhism talks about emptying the mind in the context of meditation. This is a painting by the Chinese artist Gao Qipei:

You’ll notice that a poem is inscribed at the top of the painting (about which there’s another fascinating story, involving Bertolt Brecht, but that’s for another time).

The poem is about using a quiet mind to tell the difference between good men and evil ones. Here’s a rough translation:

“The deep clarity of the empty mind

corresponds to the vast emptiness of the sky.

All these malicious and evil men

can be seen in the stillness of contemplation.”

There is a difference between using mental clarity in evaluating someone’s personal ethics and in knowing intimately whether the kimura is available, but how you get there is the same: slow progress over time, culminating in the acuity to know instinctively what to do when the time is right.

Besides, every discipline has different aims, some of which exist beyond good and evil. To paraphrase Ash from the Evil Dead films: “Good, bad. I’m the guy with the heel hooks.”

The idea of mushin is divergent from daily life experience for most of us. We work day jobs that require constant attention. Whether you’re sitting in an office or waiting tables, your mind is active and thinking about minute details. If the world slows down in these spots, it’s not because of the flow, it’s because the quotidian is making you watch the clock.

What does this all mean? It means that the New Year is almost here, and with it, I’m thinking my annual thoughts about what to improve during the next trip around the sun.

I always play the Lawrence Arms song “100 Resolutions” at this time of the year, because the chorus is something to aspire to. You can see why it’d make me think of mushin:

This year I’ll try not to think too much.

This year I’ll try to stand up for myself.

This year I’ll live like I’ve never lived before.

This is my year, for sure.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pBQc4fwj33c

This year I’ll practice more. Not just jiu-jitsu, but all the things that get me away from clock-watching and toward quiet. This year I’ll flow more and force things less, and I’m not talking about while rolling. The world will always make waves in my life, but I will learn to surf them better.

These are all things I wish for you, too. Happy New Year, everyone.