How To Get Better At Learning Jiujitsu (With Notes & Drilling)

As my future father-in-law says: you pay for everything with either money or time, and sometimes both. Ideally, you should maximize your return on all investments.

If you go to class three times a week, you’re probably spending at least 7 hours of your life (and your monthly gym dues) trying to learn jiujitsu. Maybe you’ve had the experience of learning a move, being interested in it, playing around with it … and then two months later, you have no clue what happened, and six months later when your instructor shows you the move again you slap your forehead because you forgot you’d even seen it.

Or take going to a jiujitsu seminar, for another example. If you spend $65 and two or three hours of your life to learn from Dave Camarillo, for example, you probably learned a lot. You’ve invested time and money. What if someone told you just a little more effort could cement that knowledge in your mind, expanding your repertoire over the long term?

Well, that someone is me. Continue reading “How To Get Better At Learning Jiujitsu (With Notes & Drilling)”

All Time Most Common Submissions At US Grappling

The world is made of probability. If you make consistently good choices, you have much better chances of getting good results. If you make consistently bad choices, you will probably end up getting submitted.

Numbers can guide us on what choices are better than other choices. If you ask a human being what the best technique for you to learn is, that human being is going to give you an opinion — and you should carefully consider the weight of that one person’s opinion. But while all humans have bias based on their own experience (I am much more likely to encourage you to learn the moves that I know, am good it, and have good experiences with), data is cool and rational and, if you have enough of it, going to give you a broader perspective. It’s not going to reveal everything, of course, but the more quality information you have, the better you’ll be able to make informed choices.

That’s why, with the help of U.S. Grappling, I analyzed data from more than 4,000 submission-only matches since the beginning of 2015. I wanted to have a clear and comprehensive picture of what worked most often in these true submission-only environments, with no points, advantages or time limits. Continue reading “All Time Most Common Submissions At US Grappling”

Visualize It, Don’t Criticize It

This morning at 6 a.m. jiu-jitsu class, I talked about iterated algorithms. Let me apologize here to all of the students that I hit with that number before daybreak or coffee, and thank the one person who nodded vigorously when I asked “does anyone know what an iterated algorithm is?” (An algorithm that’s been iterated. Duh).

I’ll get back to math-nerdiness in a moment, but let’s start with peer-reviewed study nerdiness. Why should you keep reading? Because this post is about a very simple way that you can improve competition performance — with minimal effort and no risk of injury. You can even do it if your time at jiu-jitsu class is limited. That simple method is visualization.

When I say visualization, here is what I mean: you use your mind to visualize the way you want your match to go. When I’m preparing for competitions, I do this a lot during my off-the-mat time. In fact, I’ll be doing visualization constantly all the way up to my time in the bullpen preparing for tournament matches. I’ll visualize myself doing all the techniques that I’d do if the match goes exactly the way I want it to: single leg takedown, knee cut pass, knee drive to mount, mounted collar choke. In my mind’s eye, I guide myself through all of these steps.

To name one benefit, it helps me be calm and focus in that nerve-wracking time before I step on the mat. But there are more benefits, and study after scientific study has shown that using visualization techniques has myriad benefits, including improving sport-specific skills, improving strength and coordination. Bluntly, visualizing a guard pass will help you pass the guard more effectively.

Skeptical? A host of studies bear this out, on topics as widely varied as strength training, golf, judo and other skills-based competitive activities. While I’m hardly an expert on this research, I’ve read more than a few studies on the topic. There is a broad general agreement on the fact that visualization has benefits, although the theories about why these benefits exist vary. But you don’t care overmuch about the why, do you? You want to pass the guard better. You want better results.

So let’s get you there. First, I’m going to review some of the visualization studies I’ve read. That’ll hopefully convince you that this is a thing you should be doing, because this is rigorous, peer-reviewed research. Second, I’m going to tell you my method of visualization, which hasn’t been tested by anybody, but seems to work for me. Then we’ll get back to iterated algorithms. How can you not stay to the end after that teaser?

Here’s the big picture: many, many different studies have been done on this, trying to establish whether we can prove that visualization effects are real. I’ll get into the specific studies in a second, but sometimes the most convincing evidence is a review that takes into account a bunch of research. Let’s say, for example, someone did a meta-study that examined more than 20 research projects into visualization’s effects. If they found a general trend toward major benefits, that would tell us something, no? Check this out:

Empirical research suggests that mental practice may enhance the performance of motor skills. Many variables have been shown to mediate the size and direction of the mental practice effects. The purpose of the present study is to provide an overview of research examining the role played by these variables in mediating the effectiveness of mental practice. In order to integrate the findings in the literature and to further analyze the relative contributions of each of these variables, a meta-analysis was performed according to the procedure outlined by Smith, Glass, and Miller. Twenty-one studies that met the criteria of having both an adequate control and a mental practice alone group were included in the meta-analysis. The forty-four separate effect sizes resulted in an overall average effect size of .68, (SD = .11) indicating that there is a significant benefit to performance of using mental practice over no practice. (emphasis added)

In summary, scientists picked 21 of the best studies they could find, and those studies had to have a way of determining whether mental practice alone could be shown to have a benefit. In those studies, there were 44 “effects” shown from visualization. And while these effect sizes varied, they were found to show clear and significant benefits to performance across the board.

Whenever I read a single study, my inner skeptic tells me to be cautious of the conclusions. You can find one study that says virtually anything you want it to. When it’s a couple of dozen well-designed studies across decades, you get on much more solid ground.

If groups of studies are more convincing, specific studies are more fascinating and evocative. Just check out the narrative from this guy’s thesis, describing a couple of important research projects and their conclusions.

In addition, Eddy & Mellalieu (2003) elaborated that the use of imagery techniques to imagine performing a specific sports skill has been shown to improve the physical performance of that. Using the mind, an athlete can register positive images over and over, enhancing the skill through repetition or rehearsal, similar to physical practice. Therefore, with mental rehearsal, minds and bodies become trained to actually perform the skill imagined. Imagery and visualization is the development of creating a mental image or goal of what he/she wants to happen or feel. Research by Newmark (2012) supports visualization was first applied to sports performance after the 1984 Olympics, when Russian researchers studying Olympic athletes found that Olympians who had employed visualization techniques experienced a positive impact on their biological outcomes and performance. (emphasis added)

To a certain extent, this is intuitive. Our brains run on electrical impulses, and using our brains to visualize, say, a sweep, seems like it should get the right patterns set in our brains. Besides, most of us spend an all-too-brief time actually on the mats during the week. The knowledge that thinking about the motion of shrimping while you’re sitting at your desk might improve your jiu-jitsu is powerful. While there’s certainly no substitute for hard physical training, it’s helpful to know that mental training — which you can do anywhere — can afford additional benefits.

When I say “benefits,” I’m talking sport-specific benefits. Take golf, for example. Two different studies tracked golfers on their putting accuracy: one found “significant performance improvements” in putting from visualization, and the other found that “using positive imagery” (i.e., imagining a successful putt instead of a missed putt) had a “significant main effect on performance improvement.” We’re talking a very specific motor-skills task here, folks: visualizing yourself striking a putt and having that putt go in makes your putting more likely to be accurate.

It’s not just golf, of course. Martial artists will be thrilled (and hopefully unsurprised) to learn that visualization while training judo not only helps you learn judo techniques, it also helps your “imaging” knowledge, your ability to successfully visualize. Like any task, the more you do it, the better you get at it, and the more you think about it, the better you get at thinking about it. When you put it that way, it seems like common sense, right?

Finally, one study that really blew my mind — and, to some researchers, hints at the mechanism by which visualization works. It’s one thing to talk about visualization improving your body’s coordination. But research shows that it increases your actual muscle strength as well. Read that again. Visualizing muscle movement actually increases your muscle strength. You remember in the Matrix, how Keanu Reeves had never used his muscles before, but he still could, y’know, move? Turns out that’s not so unrealistic.

Researchers asked 30 young, healthy volunteers to participate in the study. Eight of them were trained to perform “mental contractions” of their little finger muscles, without actually moving the muscles. Eight other people did the same mental task, but with elbow movements. Six other volunteers actually did the finger muscle movements instead of thinking about them. Then the remaining eight weren’t trained at all, physically or mentally, and served as a control group.

After the 12 week study concluded, they found this:

At the end of training, we found that the [mental-only finger movement] group had increased their finger abduction strength by 35% (P < 0.005) and the [mental-only elbow flexion] group augmented their elbow flexion strength by 13.5% (P < 0.001). The physical training group increased the finger abduction strength by 53% (P < 0.01). The control group showed no significant changes in strength for either finger abduction or elbow flexion tasks. The improvement in muscle strength for trained groups was accompanied by significant increases in electroencephalogram-derived cortical potential, a measure previously shown to be directly related to control of voluntary muscle contractions. We conclude that the mental training employed by this study enhances the cortical output signal, which drives the muscles to a higher activation level and increases strength. (emphasis added)

This tells us that yes, physical exercise is best for building muscle — but mental training can build strength, too. The mind is powerful.

One caveat: the practice of visualization in these studies isn’t standardized, so there’s some variability in how people use terms like “visualizing” and “imaging.” This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it: in fact, if that judo study is to be believed, the more you do it, the more efficient you’ll be (just like jiujitsu itself).

Rather than take you through all the methods used in these studies, I’m going to tell you how I do it, why I do it that way, and what that has to do with an iterated algorithm. I haven’t been the subject of any research studies since I was a kid, so I can’t prove what I do works, but it makes me feel more prepared, and that’s valuable in and of itself.

Given that the research shows that positive imagine has a greater impact — and that Marcelo Garcia says “I don’t worry about what the other guy’s going to do” — I start out by visualizing my ideal match, where everything goes right. I see myself doing the techniques that I’d choose to do if everything works perfectly. For me, those techniques are:

Single leg takedown > Knee cut guard pass > Knee drive pass to mount > Mounted collar choke

What can I say? I’m a simple man who likes choking with his hands. This plan, given the techniques I know and do, is my optimal world. Obviously, you can change it up and insert your ideal match techniques as well. I run through these techniques in my mind over and over before my match.

As we all know, no plan survives engagement with the enemy. Often, people are pesky, and they don’t let you just dominate them from stem to stern. Plus, sometimes I just choose to pull guard. And finally, it’s boring to imagine the same match in the same order over and over.

An iterated algorithm is a concept from math. You start with a number (or point), then process it somehow to obtain a new number or point. When you integrate that new number/point into the process, you create a “feedback mechanism” — and after a while a pattern emerges.

You can think of how I do visualization as several iterations, or, if you prefer, a Choose Your Own Adventure book. I start from the ideal match (Single leg takedown > Knee cut guard pass > Knee drive pass to mount > Mounted collar choke). Then, I insert some changes into the system. What if I get taken down? Maybe it’s:

Get double legged > Recover guard > Tripod sweep > Knee cut guard pass > Knee drive pass to mount > Mounted collar choke

Or what if the process is disrupted in the middle? Maybe he recovers guard, and I have to pass again:

Single leg takedown > Knee cut guard pass > He recovers guard > Torreando pass > Back Take > Bow & Arrow Choke

You can see that the possibilities are infinite. But two commonalities remain: first, I always visualize finding a way to win the match; and second, I keep the visualizations to my A-game techniques, the most likely tactics that I’ll have to use. This keeps all my best options in the top of my mind. It also gives me something to do in the bullpen, which is nice.

In most competitive pursuits, the person who is able to impose their game on the other party wins. This is why drilling and rolling are both important: getting to your happy place quickly and efficiently is critical.

If you want both your mind and your body to get to that happy place more often, try visualization. No iterated algorithms required.

What Were The Top Submissions of 2015?

There are two reasons I wanted to analyze all the matches from US Grappling‘s points tournaments last year. The first: examining big-picture trends can tell us a lot about what works in practice, what people are doing, what we need to be drilling and what we need to be alert about defending.

The second reason is that I am a giant nerd, and I love data, and I wanted to talk about data on the year-end Cageside ConcussionCast. I go way more in-depth over there, and you can listen to the archived show here or subscribe on iTunes. What follows is a breakdown of all the matches for which we have information in 2015.

To get this, I went through all of the scanned brackets that were available (thanks, Brian & Chrissy Linzy) and put the results into a Google Spreadsheet for ease of data manipulation. There are some caveats about this data, but only super-nerds care about that, so I’ll save them until the end. What you really care about are the results, so let’s get into them.

SUBMISSIONS ARE SLIGHTLY MORE LIKELY THAN POINTS

Generally speaking, about half of US Grappling matches go to points. Of the 2091 matches I analyzed, about 1100 ended in submission, so slightly more than 50 percent end with taps. If you’re betting on whether a match will have a submission or not, you’re slightly better off betting “yes,” but keep in mind that you’re better off betting on points than on any specific submission. Even the armbar. But if you’re going to bet on one submission …

ARM BARS RULE, & SO DO HEEL HOOKS

The arm bar is the most common submission in every division group except one, which is 30+ men’s nogi, where it runs a close second to the Rear Naked Choke (RNC). The armbar is still king in the Men’s Purple to Black belt gi divisions, but it’s close: the arm bar beats the bow & arrow choke by a narrow margin.

(To avoid confusion on something I say below, when I say “division group,” I mean “Men’s NoGi, Women’s Gi,” and those larger groups. The arm bar isn’t the top submission for Men’s Advanced NoGi, for example, but it is the top submission for Men’s NoGi generally. I broke the data down this way for sample size purposes.)

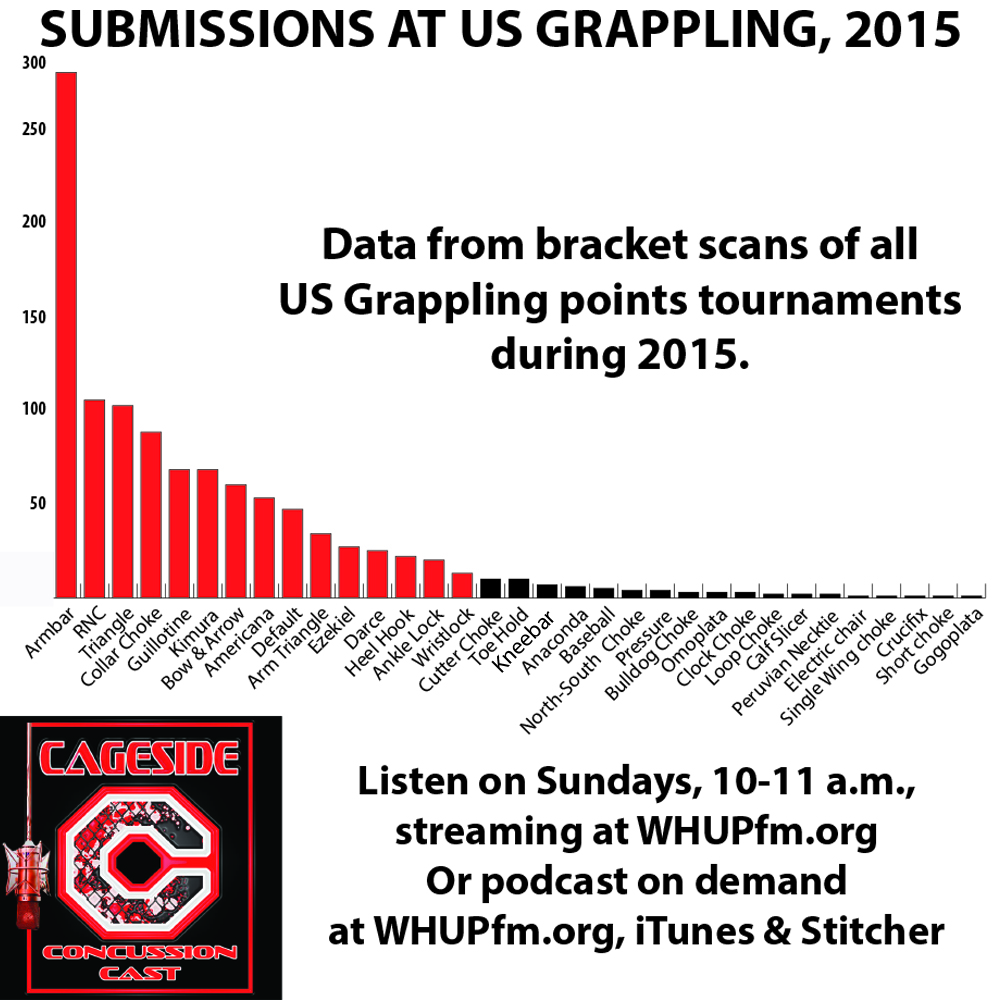

Here’s the chart of all the most common submissions, in order, with the top 15 in red:

Of course, the arm bar is allowed in every division, so that gives it an advantage in terms of pure numbers. We’d expect the main submission to be something that every division, gi or nogi, white belt to black belt, can do. We wouldn’t necessarily expect the arm bar to be this far ahead of everything else, though, so that feels significant.

A related point: chokes using the kimono can only be done in half of the divisions, so they’re way more powerful than they look from this chart. The good old-fashioned collar choke performs very well, as does the bow & arrow, especially in the upper belt divisions. The same applies to leg locks. Aside from the straight ankle lock, only upper belts get to use them.

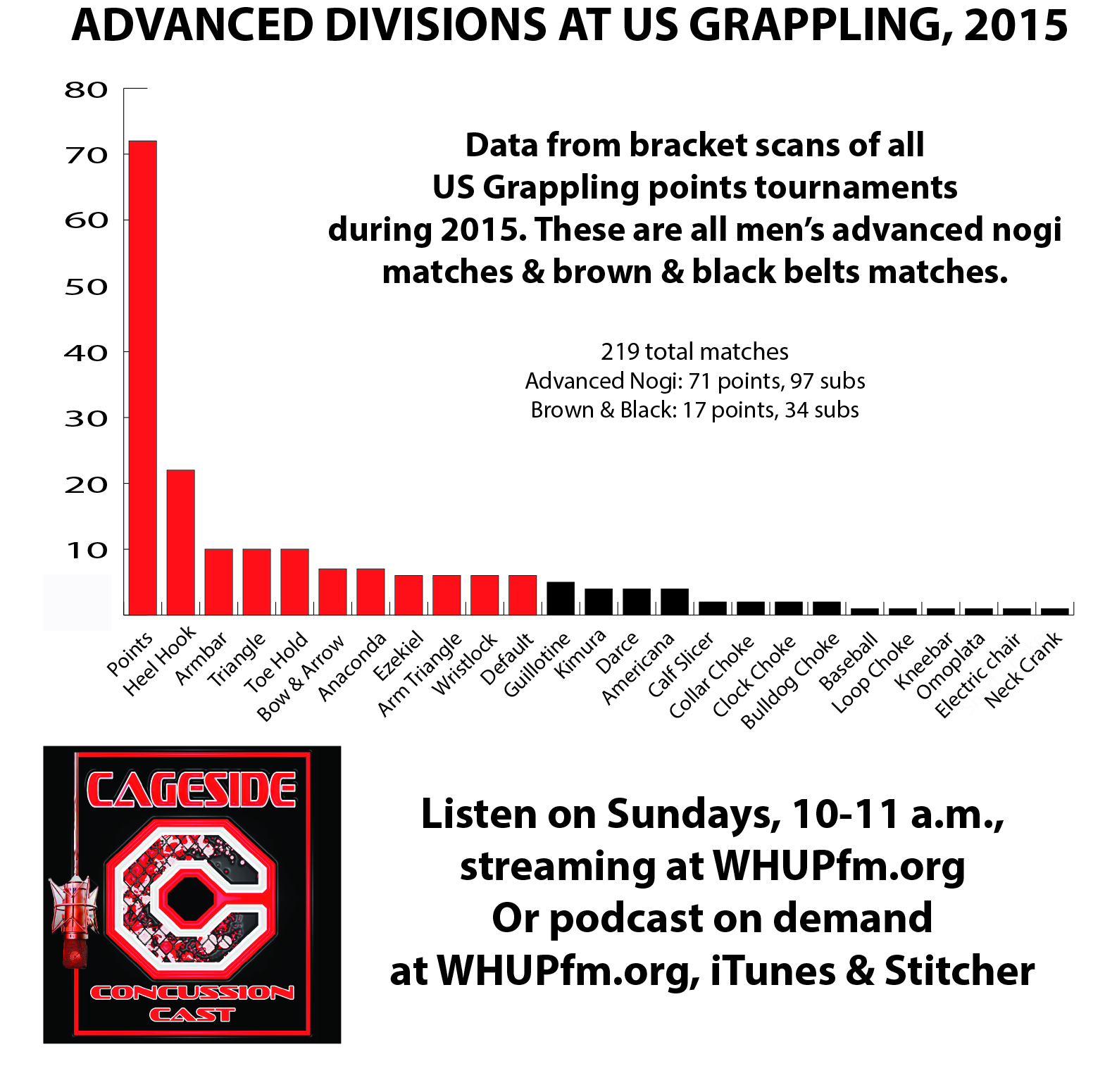

And if you break the data down into specific sub-divisions, you see how powerful the heel hook is. It’s only allowed in adult advanced NoGi, and yet there were 22 heel hook submissions — more than twice the next-most common submission. By the way, there were also 10 toe holds and a couple of calf slicers, so hide your feet in adult advanced.

FUNDAMENTALS WINS TOURNAMENT MATCHES

Here are the top five submissions. Let me know if you see a common thread.

Armbar: 279

Rear Naked Choke: 105

Triangle: 102

Collar Choke: 88

Guillotine & Kimura (tie): 68

That’s right: the most common submissions are all moves you’re going to learn in the first six months. That stuff doesn’t stop working. Keep drilling it.

Yes, fancy stuff happens. We had an electric chair submission (what’s up, Marcel Fucci?). A gogoplata (what’s up Alec Cerruto?). And two Peruvian neckties, in the beginner division and white belt division (stop watching YouTube, guys). But for the most part, it’s the basics that get it done.

To give you an idea about this: the 6th most popular submission is the bow & arrow choke. There were more bow & arrows than the bottom 17 submissions combined, including all the funky stuff.

MORE POPULAR THAN I THOUGHT

Wrist locks. The dandy is back with a vengeance, getting 13 submissions. That’s twice as much as the baseball choke. Cutter chokes are also more popular than I would have guessed: there were more cutter submissions than the North South choke and the Anaconda choke combined.

LESS POPULAR THAN I THOUGHT

Three omoplata submissions all year. Yes, most people use the omoplata as a sweep. And maybe this is because it’s one of my favorite moves, but there were as many bulldog chokes (3) as there were omoplatas, which surprised me.

UNDER PRESSURE

There were four taps to pressure last year. The surprising part about this: three came from blue belts, one from a purple belt. There were more taps to pressure last year than taps to clock chokes (3, two by Jake Whitfield) or loop chokes.

30+ MEN GET HURT AND WOMEN ARE TOUGHER THAN MEN.

I rolled injury, default and disqualification into one category (and there was only one DQ that I remember counting) so this number tabulates matches ending in injury and people not showing for the next match, either due to injury, fatigue, or whatever.

The realities of our bodies: they get more fragile as they age. Another reality: one gender pushes out babies. Thus, it should be no great surprise that older guys (like me) get hurt at a higher rate and women just don’t default from matches at anywhere near the rate guys do.

Let’s start with the old guys: of the 47 total men’s division defaults, 17 were 30+ men. There were 441 30+ men’s matches. One in 26 of those matches had an injury default. This is still not a huge rate, given that we try to bend each other’s joints the wrong way, but it’s far and away the highest rate of the groups I looked. By contrast, the total injury rate for men is one in 38.5 matches.

What about the women? 282 matches, four defaults. FOUR. That’s about one in 70 matches. And it gets more impressive: I was reffing the tournament where two of those defaults took place, and at least two of them were closeouts. That’s when two teammates meet in the finals and choose not to compete against each other, meaning those were non-injury defaults as well. In reality, that number is more like 1 in every 140 matches.

Granted, this is a small sample size. But still, it’s worth noting. Women of jiu-jitsu, Kathleen Hanna and I tip our caps to you.

ADVANCED DIVISIONS SHOW MUCH THE SAME TRENDS, BUT WITH LEG LOCKS

So, when you break the data down further to just a few advanced divisions, the picture changes slightly. I grouped the information from adult advanced NoGi and brown & black belt gi divisions.

The results: armbars are still powerful, but leg locks really change the game. Heel hooks are very common, and toe holds aren’t far behind. (Also, big surprise: in 219 matches, zero rear naked chokes or straight ankle locks.) Consider this, too: advanced grappling matches are slightly more likely to end in submission than other matches, from this sample. Out of 219 total matches, 131 ended in submission. Interestingly, in a fairly small gi sample of 51 matches, there were twice as many taps as there were matches that went to points (34 to 17).

To close this out, let me show you the broad division groups I put the numbers into. I combined them this way for sample size purposes.

Here are the top five submissions for each broad division group:

| Men White & Blue Belt Gi | Men Purple to Black Belt Gi | Men NoGi | Women Gi | Women NoGi | 30+ Men Gi | 30+ Men NoGi |

| Armbar | Armbar | Armbar | Armbar | Armbar | Armbar | RNC |

| Collar Choke | Triangle | RNC | Collar Choke | Americana | Collar Choke | Armbar |

| Triangle | Bow & Arrow | Guillotine | Americana | RNC | Bow & Arrow | Kimura |

| Kimura | Ezekiel | Heel Hook | Bow & Arrow | Guillotine | Triangle | Guillotine |

| Bow & Arrow | Collar | Arm Triangle | Ezekiel | Kimura | Kimura | Arm Triangle |

By the way, if I put “Default” on here, it’d be the No. 3 submission for men’s 30+ in the gi.

FINALLY, A NOTE ON THE DATA

Any project has limitations, and I want to acknowledge them. For one thing, this only tabulates the points tournaments, not the US Grappling Submission Only tournaments. If there is enough interest, I’ll do a post about those as well. Also, some data is missing: the majority of table workers did a great job with writing down results, but there were many brackets with either no information about how someone won, or the information was vague (“verbal submission,” but not what submission). So I didn’t include the information if it wasn’t reliable.

There are also issues with terminology. Some of this is easy. I rolled “keylock” and “Americana” into one category, which is obvious, and “Darce” and “Brabo” into one category. But there is also the more vague “shoulder lock,” which ended up getting counted as a kimura. And the whole “collar choke” category includes all collar chokes, because the brackets don’t specify from mount or from guard. That’s information I’d like to have, but we just don’t have it. Then, you have the possibility of transcription errors, so we should take this for what it’s worth: a fun look at big-picture data.

I guess I’m saying this: Before you use it for your master’s thesis, maybe hit me up with an e-mail. Thanks for reading!

By the Numbers: the Mundials

On the topic of data visualization, the folks at Bishop BJJ have put together a first-of-its-kind breakdown of statistics from the Mundials. You can see from my last post why this type of information would fascinate me — all the more so because I competed at the tournament this year.

Sign up here and they’ll send you the PDF file. It’s chock full of great information.

My next big graphic project is compiling data from US Grappling tournaments and making infographics. If I think the results are interesting, maybe I’ll do a post comparing the US Grappling events to the Mundials in terms of data results.

… OK, done with the data nerd stuff for a while. We now return you to your regularly-scheduled grappling stories and whatnot.

A Tournament in a Picture

… or a graphic, actually. I’ve been taking a data visualization class, and I thought I’d try to represent the results from US Grappling’s latest tournament in image form. It’s the from the State Line Grappling Championships in Bristol, TN.

If you click here to get the full-size version, it should be pretty intuitive, but I’ll explain anyhow. Each bubble represents a match: the bigger the bubble, the longer the match went. Each bubble is color-coded by how the match finished.

I’m going to be trying to produce more of these after each tournament, so if you have comments — including suggestions for how to represent the data better — please offer ’em up. These are fun projects that allow me to combine BJJ with my inherent data nerdhood.